|

Few things are more exciting to me then when "good parenting" is validated by science! Perhaps it's a throw-back to my early interest in chemistry and fascination with Albert Einstein. Even if science isn't your thing, if you are a parent, this information will be of interest to you. Read on.

Isn’t it great when science validates something we intuitively know? Such is the case with Dr. Michael Meaney, a professor of McGill University with an interest in maternal care, stress and gene expression. In the Annual Review of Neuroscience he published work centered on the natural variation he noticed in licking and grooming by mother rats. He found that the kind of care that mother rats provide to their offspring alters genes responsible for stress response. The rat pups who experienced more licking and grooming were identifiable by the anatomy of their brain. When Meaney followed the rat pups into adulthood he found that those who were licked and groomed were better at completing mazes and even lived longer. The mechanism at play is that those pups who were licked and groomed produced fewer stress hormones when faced with a challenge. This is important, because he know in humans, when our brains are bathed for too long in stress hormones we are always “on alert,” anxious and exposed to an increased risk of mental health issues, heart disease or diabetes. We want our stress hormones to kick in when we are in danger, then dissipate. The licking and grooming provided to rat pups served as a protective factor and prepared them to manage stressors into adulthood. What to parents of rats and parents of humans have in common? The capacity to provide affection and physical touch to their offspring. Dr. Meaney uses the implications of his work to note “Women’s health is critical. The single most important factor determining the quality of mother-offspring interactions is the mental and physical health of the mother.” This is true regardless if the primary caregiver is a mother, father or even grandparent. In subsequent research Dr. Meaney paired mothers who scored high on licking and grooming with rat pups who were not their biological pups and the outcome was the same. We have opportunities daily to engage with our children in a way that will better prepare them to ride the wave of adulthood in an emotionally healthy way. What does licking and grooming look like when you are in parenting a human rather than a rat? Good question. Many of the things you are already doing, for example, lotioning your child after a bath, playing patty-cake or “this little piggy.” Theraplay is a clinical intervention focused on building attachment between parents and children. One of the domains of focus is nurture, which is all about physical touch and expressing to the child “you are worthy of good care.” Some Theraplay activities include lotioning, which can be used as a variation for an older child. Start by placing dots of lotion along the child's arms, or face and slowly rub in each dot. Creating a secret handshake with your child. Giving your child and manicure or pedicure with a focus on physical touch and nurture. Face painting, a thumb war, mirroring, peek-a-boo. Using your finger to draw letters on your child’s back and see if they can guess the word. Create a variation of a song for your child, Theraplay uses Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, with a twist “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, what a special boy you are, dark brown hard and soft, soft cheeks, big green green eyes from which you peek…. As you can see many of these activities are built into the way we interact with children already. By being conscious to include them in your daily routines you and your child will benefit. So, the next time you snuggle a newborn, or force your third grader into a hug, feel proud that you are having an impact--on a cellular level. **This was first published by familyshare at: http://www.familyshare.com/Parenting/biochemistry-of-good-parenting. Announcing an excellent way to ring in the New Year!

Social Skills Group

January 5th -February 9th 2015 Investment: $150 Where: Whitney Barrell’s office 684 e Vine Street Murray, Utah 84106 801.502.5644 **feel free to call with questions, or to see if your child would be an appropriate fit. Welcome Readers,

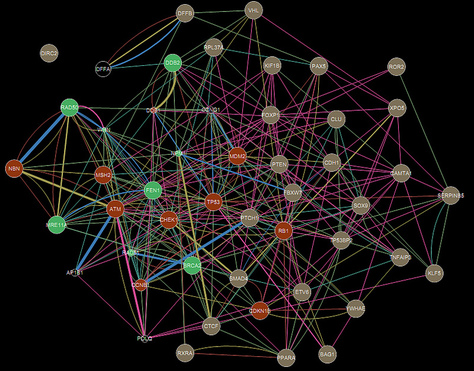

Below you will find an extended version of the article published by KSL. Please enjoy! As a child therapist, I often wonder what sets apart the children who are able to manage and thrive in adverse environments plagued by adversity, abuse and poverty, from those who seem to succumb to it. But, resiliency doesn’t have to mean the ability to bounce back from such extremes. Some children are just more flexible, able to pick themselves up and dust themselves off. Resiliency is a fascinating subject of study pertinent to parenting. In 2005 Human Development specialists Thomas Boyce and Bruce Ellis published a paper in the Journal of Developmental Psychology which provided a metaphor for a phenomenon they were seeing in their study of kids susceptibility to their family environment. They noted some kids were “orchids” and others were “dandelions”. Dandelion children can grow anywhere, they seemed to have the resilience to survive through difficult family life, poverty, abuse. The orchid child is highly sensitive to their environment, specifically to the type of parenting they receive. Those who are neglected by parents, either physically or emotionally are impacted in the long term as measured by teenage misbehavior including aggression, drug abuse and delinquency. Although, those same children who are nurtured- flourished. This was an interesting finding, it was a novel idea that that the orchid children had the capacity for both positive and negative outcomes. Long story short--researchers found variants in the children’s CHRM2 gene which interacts with the child's environment. When the variant is combined with poor parenting, these children exhibit outcomes such as aggression and delinquency. But, children with this same variant combined with attentive parenting were shown to have positive teenage outcomes. The take-home is that whether or not your child is a “dandelion” or a “orchid” it’s in their best interest to develop a sense of inner grit. We know that resiliency has factors that are functioning at a cellular level, but we also know those factors are impacted by our environment. And, as parents, we have some control over our child's environment. Undoubtedly, children are going to experience some sort of hardship in their early life. We can hope for bullying or the difficulty of transitioning into a new classroom vs. the more serious, abuse or loss of a parent. Children who are able to rebound from adversities are healthier psychologically, show better outcomes academically and socially. Resilience turns out to be a life skill, and research by the American Psychological Association as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics has shown it’s something we can cultivate in our kids. Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia authored a guide in collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics focused on building resilience in children and teens. They’ve outlined several factors that parents can instill in their children. Connection It’s not a surprise that adults who have a network of friends and family to call on in times of stress show less mental health issues, live longer, and have fewer chronic health diagnosis. That being said, social skills are learned and childhood is the time for practice. By providing ample opportunity and modeling pro-social skills, your children will be on their way. The more stable, nurturing adults a child has to rely on, the better. Connections to others serves as a protective factor for children at risk. We know that if a child has just one person who consistently offers caring, unconditional support they can use that foundation for healthy development. Competence Empowering children to make their decisions builds mastery. If your child chooses a hobby, support them in this endeavor, provide resources and encouragement. Children who see that they are successful in a specific area of life feel hopeful and in control. Children are likely to see that if they have skills (reading, writing, getting along with others, problem solving) then they are more optimistic when facing a new barrier. This is also true even if the skills they excel at aren’t transferable to the task at hand. Contribution Children who see that they have an influence on the world are more resilient. Encouraging your child to contribute to others will provide them perspective, gratitude and an understanding that they can make an impact. Contribution builds a sense of purpose, which is important for persistently moving towards a goal, and feeling that its attainable. Coping The best way to teach your child positive coping skills is to use them yourself. Sometimes I suggest parents of young children to verbalize “I'm upset and I’m going to take a few deep breaths to calm down.” This is the ultimate way to “walk the walk.” Guiding your child through the inevitability of disappointment and sadness is a way to show that life goes on. Additionally, pointing out that your child has managed difficult situations in the past helps to build competence. Talk through a resiliency inventory. Ask your child to recount a time there was a challenge in their life? What did they do in order to both survive and thrive? Ask if any of these skills can be used currently. We all want our children to succeed and one of the best predictors is a strong sense of self. Children who are resilient feel that they have the tools and support to deal with upsetting events. As parents we can’t control what comes at them in life, but we can help them to build their response to it.

The first day of school is upon us, and many children are returning to school or starting their first day of kindergarten. This is a stressful time for children (and parents). Separation anxiety is common in school-age children. It is characterized by persistent or excessive worry about separating from a child’s primary caregiver. This translates into the dreaded emotional drop-off, a child who won’t get out of the car, they are pulled, tearful, into the school building only to scream as their parent walks away. We’ve seen it or we’ve been “that parent” only to return to our car and have our turn at crying. Not fun for anyone.

Even if your child isn’t excessively worried about going off to school, some of these techniques can ease the transition.

Lastly, be aware of your own feelings. Are you as scared about your child leaving you as he is? Your child may be picking up on this, and reacting to it. Try and talk through these feelings with another adult (not your child) so that you can be emotionally available to your child. If your child is struggling to transition into school, know that it’s normal and for most children is resolved in the first few weeks. Sometimes I can hear it in a parent’s voice when they first call to make an appointment, the trepidation, the guilt, the anger. “My kids is out of control.” They may describe a child being suspended from school or day care, or being tearful all the time. Often times the root of these concerns comes down to emotional regulation.

Emotional Regulation is a skill that isn’t innate, we learn it, we watch those around us for cues on how to do it. It takes practice, just like anything else. Generally we get better at it as we age. Think of a newborn, the response to pain, sadness, unmet needs is all the same, crying--it’s the only form of communication they know so far, and it’s highly effective. As children age they develop more sophisticated ways of managing strong emotions. In play therapy I see it as one of my primary goals to teach children feelings identification and expression. I use role plays, sand tray, puppets and games to accomplish this. A child who acts aggressively or loses control and throws crying fits are still trying to fine tune how to express “big feelings.” I often see this in the school setting, teachers are frustrated with children who act out, and typically these same children struggle with social connections because their emotions are so unpredictable. If you are nodding your head, thinking, that’s my boy! You are not alone. This is a very common concern parents report during our first visit. Parents tend to feel instant relief just reframing this concern into a need for skills, rather than just “bad behavior.” As I stated, emotional regulation is learned. I suggest that parents begin with this one subtle intervention. - Label emotions for your child For example, your daughter sulks away to her room and avoids everyone in the house, she begins crying and kicking the wall. You might say “You seem like you might be sad about something?” This not only validates her feelings and shows that you are noticing, but it may put a word to a complex emotion she is feeling. This is a starting point for regulation emotion, connecting the feeling inside your body (lump in throat, tears, weight on your chest) to the emotion. As adults, we forget how difficult it can be to navigate life as a child when “big emotions” do come up. Typically, by the time we are adults we’ve accrued quite a toolbox of things to do when we are upset or overwhelmed. Children are just building this tool box. When they are faced with events in life that stir up an emotional response (whether that’s something as simple as not liking what’s for dinner, or the death of a parent) they are using the tools they have so far. Life tends to constantly feed us experiences where we learn more effective ways to cope, kids are on that road too. As a child therapist it’s my job to join them and provide some hands on ways to improve these skills. Good Day, Welcome KSL readers! Today KSL has published an article in which I outline the common reasons that parents bring their children to therapy. I also attempt to decrease some of the stigma related to child mental health. Head here to read it! Or, I've also provided it below. Could my child benefit from therapy?

For the majority of children, the answer is no, but if you are wondering, read on. As parents, our primary goal is to nurture and protect our children. When we consider that our child may benefit from mental health intervention many of us feel overwhelmed, guilty or ashamed. But this need not be the case. Life happens, and it happens to children too. Therapy is a safe place to explore difficult events from the past or learn new life skills. Play therapy has some similarities and some differences from traditional talk therapy. For example, we know that children make sense of the world through play. Additionally, their cognitive mechanisms are not fully developed yet and therefore focusing interventions purely based on talking and the use of language is less effective. We use play to bridge this gap. When we consider that our child may benefit from mental health intervention many of us feel overwhelmed, guilty or ashamed. But this need not be the case. Life happens, and it happens to children too. Play therapy relies on parents' input and cooperation. You know your child better than anyone else. You have the relationship and opportunity to best assist your child. Consider the therapist as a coach who provides instruction on things to do at home. Many parents wonder if their child may benefit from therapy. There are several common reasons parents bring their children to be seen.

Lastly, children are resilient. Early identification and treatment will prevent the loss of critical developmental years. Researcher Emmy Werner has identified children that are “active, affectionate and good-natured” are better able to cope with stressful life situations. Providing your child with the tools needed to work through this sometimes unpredictable world will benefit them for years to come. Whitney Barrell, LCSW, has a master's of social work from the University of Utah. In her private practice she enjoys working with children and families on myriad mental health issues. She can be reached atwww.whitneybarrellcounseling.com. Hello out there! I am a frequent contributor to KSL, Family Focus and other news organizations with a focus on family and mental health. What follows is an article I wrote which was originally published by KSL, WorldNow, Gatehouse Media Group and Fox NY on February 11, 2014. Enjoy!

Are you the type of parent who prefers rough and tumble play with your child or working together on artwork? Something in between? Regardless of what style of play you prefer, folding in some play therapy techniques can offer long-lasting benefits. Play therapists relying on the evidenced-based practice of child-directed play use letting the child lead, the sportscaster technique, limiting “teaching moments” and the use of labeled praise to improve relationships. Dr. Gary Landreth and Dr. Sheila Eyberg pioneered child-directed play therapy. It's use focuses on improving the parent-child relationship as a means to improve the child's behavior. These techniques are typically used with children ages 2-7. Researchers have long known that a good parent-child relationship (sometimes called a secure attachment) has lasting effects. Children in preschool and elementary school who have a history of secure attachment continually exceed their peers in regards to competency, empathy, feelings identification, social skills and self-confidence. Therefore, child-directed play seeks to strengthen this relationship. But these techniques don't need to be reserved for play therapy only. What parent isn't interested in instilling more self-confidence or empathy in their child. Let the child lead Child-directed play is most effective when used with games that involve imagination, or at least those without rules. For example, board games aren't amenable to child-directed play, but any type of artwork, role-playing games, blocks, games using figurines (animals, dolls) work perfect. If you see your child is engaged in this type of play, join them, but let them be the director. The pace of a child's play can be slower than adults are used to, so be patient. Sit back and use behavioral descriptions (explained below) as a way to participate. If they want you to join them, ask “which animal should I be?” Resist the urge to make suggestions or impact the direction of play. This is a role reversal for parents and children, and when it's in a safe, contained environment, let your child be the guide. Act as a sportscaster One way to let children know what they are doing is important to you is to use the sportscaster technique. This means using behavioral descriptions. Narrate your child's play as it's happening. Say “you choose to use the pink crayon.” Or “I noticed you are really focused on making a circle.” This communicates to children that what they are doing matters and that you are present with them. As adults this would bother us, and we'd question why someone was narrating our every move, but you'll be surprised how much your child eats it up. Abandon your instinct to “teach” Rather than jumping in during blocks and asking questions such as “what color is this block?” or “how many red blocks do you see,” focus on observing behavior and describing it. This is easier said than done. Many parents use every opportunity to teach their children. During this time, the focus is on letting the child direct the interactions. Use labeled praise We are quick to praise our children, but try using labeled praise, meaning specific, descriptive praise. For example, “I like the way you didn't give up when you were frustrated” rather than “good work.” When joining your child in play, look for opportunities to point out good decisions they've made, creative problem solving or examples of pro-social choices. By using labeled praise, children will gain a greater understanding of what your expectations are. Additionally, when you are closely observing your child, it's easier to pick out what you are impressed with and give your child feedback rather than when you are distracted by your to-do list. Play is the language children use to communicate their feelings. By using some of these techniques with your child, you may be privy to subtleties that are easily overlooked. Channel your inner child and enjoy. Whitney Barrell, LCSW holds a Masters Degree in Social Work and owns a private practice primarily serving children. She has extensive training and experience in working with young children. Original PostCopyright 2013 Deseret Digital Media, Inc. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed